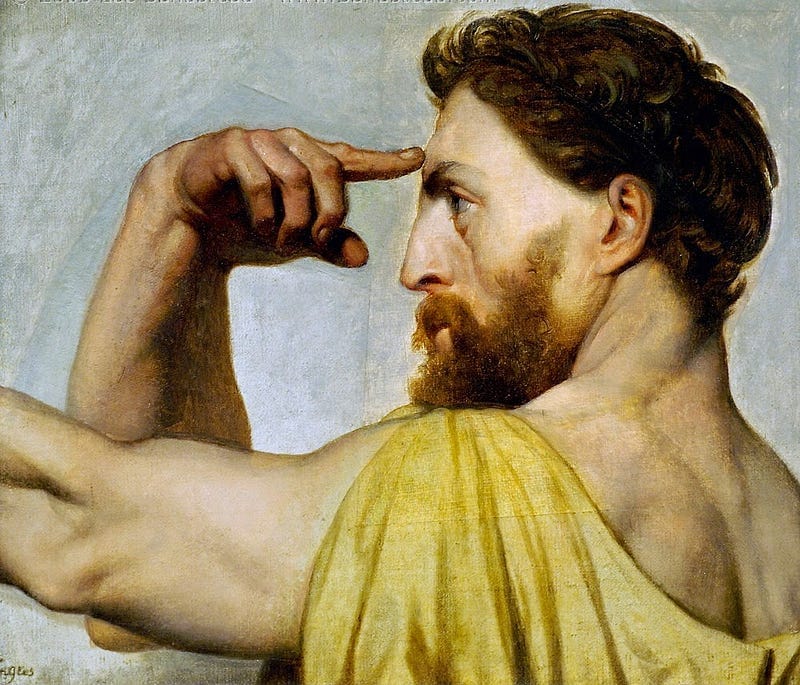

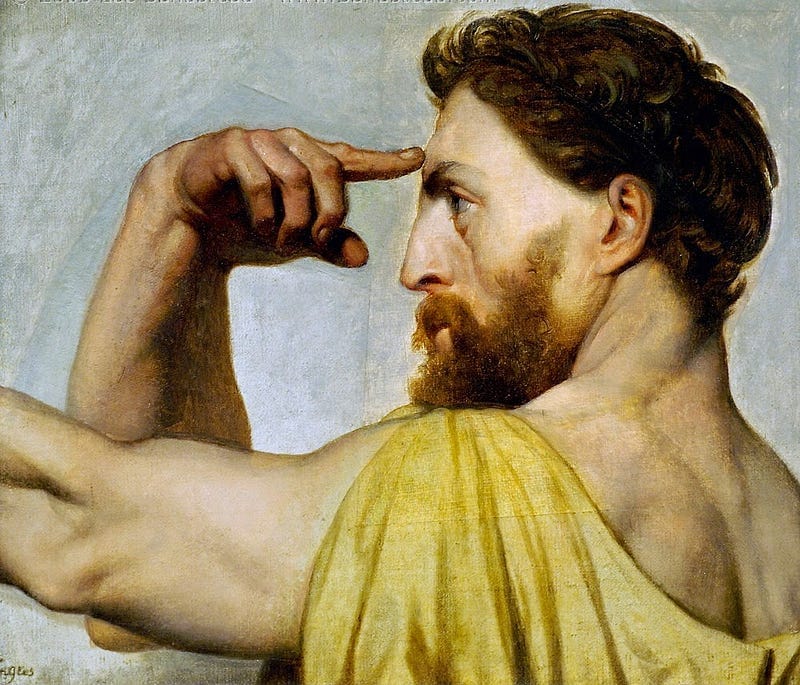

Inner Spontaneous Sound in Parmenides via Kingsley

Kingsley Calls Out The Challenge We Face From Our Own Distractedness, So Craftily Weaponized By Those That Seek To Undermine Us

Kingsley Calls Out The Challenge We Face From Our Own Distractedness, So Craftily Weaponized By Those That Seek To Undermine Us