My Heart-Felt Intention For This Book Is To Share The Complete Instructions For The Practice Of Great Responsiveness Meditation, Using Inner Spontaneous Sound, While Giving Evidence For Its Authenticity, And Discussions Of Its Ability To Protect And Guide Us During The Troubles That Are Already Here.

The primary purpose of this book is to share the use of a very important, relatively unknown, and often poorly understood support for advanced meditation, and the technique that I was introduced to at a young age, using this support for a particular meditative attainment. As I will explain, this meditation practice has a very beneficial side-effect that will help you in these troubled times.

I refer to this support as inner spontaneous sound, but there are many other names that have been used for it. You can see the list that I have taken from the teachings and doctrines of various traditions in the Glossary. Given the overwhelming number of names that have been used, I have made mine simply an indicative expression that describes the characteristics of the support: ‘inner’ means at the heart of our being; ‘spontaneous’ means that it has no cause; and ‘sound’ is its nature.

That latter word is what causes confusion in those who, upon hearing that it is sound, believe they understand it completely. This is a big downfall for those who try to teach how to use it, without having perfected the use of it in their own meditative practice. These sounds also cause confusion for dedicated meditators who suddenly find themselves confronted by these sounds, when they suddenly notice them during their own meditation.

The source of the confusion about it, lies in our habitual conflation of our experience of sound with the environmental conditions that are the stimuli for our perception of sound. All too often, this results in the misunderstanding that we can use our experience of any sound to meditate with, and we will achieve the exact same results. This is false. Our common understanding of sound is that it arises because of external conditions that cause pressure waves in the air, or other environmental mediums, which then creates vibrations in our ears, and that is sound; but these are not inner spontaneous sound.

Because of the distinction that needs to be made between ‘regular’ sound and inner spontaneous sound, there are a plethora of doctrinal explanations for what these sounds ‘truly’ are. These sounds, though, arise as a natural component of our very being, so really, they are simply that, and most attempts to explain them necessarily have to force them to conform to a pre-existing ontological paradigm.

When I first considered sharing these meditation techniques, I struggled with the myriad doctrinal descriptions of these sounds in the various spiritual traditions that mentioned them. Which should I use, given that the explanations were so different? Whose tradition should I adopt? Then, one day, I had an epiphany. I didn’t have to explain what was special about these sounds! I had to explain why our penchant for confusing external conditions with our perceptual experience of sound was blinding us to the simple fact that all sounds are produced only in our mind. Sounds don’t exist outside of us. And once I realized this, I saw something truly amazing. Traditional meditation techniques are meant to bring the meditator to a direct experience of the nature of mind, and the secret power of this support is that it does just that in the simplest way possible — it is the nature of mind on display. It’s like having a carnival barker yelling in your mind, “Step right up! Step right up and win the prize! See the amazing and wonderful nature of mind on display right in front of you!!” This support is your inner teacher.

For example, because we confuse the mental perception of sound with the actual phenomenal events that create various sorts of compression waves in the air, as well as other materials that may conduct these waves, such as the ground, we can then ask a question like the well-known koan: if a tree falls in a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound? The correct answer is “no, trees falling in a forest create vibrations in the ground and the air, not sound — only our mind creates sound.” This means that it doesn’t matter if someone is present or not — our presence, or absence has no impact on what happens when a tree falls in a forest. It only determines whether or not we will have a perceptual experience of the sound of a tree falling.

So if you can let go of that habit, and learn to identify and use inner spontaneous sound, you will benefit greatly. And if you pay attention to what scientists have learned most recently about how our experiential faculties, such as our hearing, work with externally-originated stimuli, such as vibrations in our ears, then you may come to understand why I say that all sound, indeed all our perceptual experiences, are solely mental phenomena. Then you will see how that overcomes the difficulties involved in understanding this very unique support for meditation. It is sound that has no cause. These inner spontaneous sounds, like all sounds, are produced mental phenomena.

More accurately depicted, inner spontaneous sounds are the resonances of the fundamental activity of the naturing of our being — indeed of our world. This word, “naturing,” is very important to get right, so I will be introducing it over the next three chapters. If it helps you, initially, to hold onto this idea, think of ‘naturing’ as a productive principle that replaces our common ideas about random interactions of matter over very long periods of time giving rise to complex organisms. This naturing is not an entity, and not some thing that you can point to, which is why I use a verb. It is the fundamental activity of responding to the potential ontogenetic development of organisms within the context of their environment, to actualize their being. That is, our reality is responsive, not chaotically determined. Responsiveness replaces causality, by encompassing it — a ‘cause’ is just a possibility of 100%, so responsive naturing still supports what we think of as causality, but goes way beyond that.

My point in describing these sounds, and introducing a very different way to understand our perceptions, is not to replace any traditional doctrines, but rather, to disentangle these inner spontaneous sounds from our strictly materialist ideas, theories, and language, under which inner spontaneous sound’s special value as a support is unintelligible. It makes clear what these sounds are not, so that their real difference from other meditative supports can be more clearly understood.

The meditation technique that I used throughout my life did not have a name before I started writing about it and the effects that it had on me over the years. In fact, I didn’t tell anyone about it, even when I was introducing my philosophy students in university to mindfulness meditation. Once I started writing about it, I felt the obvious need to have a name for it. After much deliberation, I decided to call it Great Responsiveness Meditation. It was a descriptive name, descriptive of the most unusual effect that it had.

“Great Responsiveness” is a translation of the Sanskrit term mahākarunā. Unfortunately, this term is frequently translated as “great compassion,” but this is wrong. “Karunā” does not mean compassion. “Compassion” means “concern for the suffering of others.” The root in the word “karunā” is “kara,” and that means “to do” or “to make” in Sanskrit, so karunā is not just a concern. It means doing something about another’s suffering — responding to their suffering. And the qualifier, “great,” elevates this responsiveness to the highest level, going way beyond the norm. This is why I decided to name my meditation as I did. It brings about a kind of alchemical change in the meditator, who begins to manifest great responsiveness towards the suffering of others. Imagine a world in which everyone helps one another. This book, and the years it’s been in development, is an example of this.

Some years after adopting that name for my practice, I discovered the Surangama Sutra. It was a very strange introduction to the sutra. Out of pure curiosity, I was tracking down the history of Jack Kerouac, who was an American novelist and a Beat Generation poet, most well-known for his book “On the Road.” I had discovered that Kerouac had lived in the village of Northport on the North shore of Long Island during two periods of his life. He moved in with his mother, who lived there, and during a later period he lived with a friend on a property just down the block from my home thirty years later. What was interesting was that Kerouac, who had stolen a book called “A Buddhist Bible” from a public library in California during his “On the Road’ years, had fallen under the spell of the Surangama Sutra that was included in that book. He took prodigious notes as he studied the sutra, carrying the book around with him wherever he went. His writings turned towards Buddhism, and his books, in which Buddhism and the Surangama Sutra’s lessons played a big part, motivated thousands of people to become Buddhist.

In his introduction to a posthumously published book of Kerouac’s, titled Wake Up — A Life of the Buddha,1 Robert A.F. Thurman2 described Kerouac as the “lead bodhisattva, way back there in the 1950s, among all of our very American predecessors,” and he labeled Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums as: “…perhaps the most accurate, poetic, and expansive evocation of the heart of Buddhism that was available at that time.” I’d like to quote Kerouac in Wake Up as he relates Buddha Shakyamuni’s use of inner spontaneous sound, referred to here as “Transcendental Sound,” as the source of his enlightenment, as well as being the source of the Dharma teachings of the Buddhas themselves, that he went on to spread widely — once again turning the Wheel of the Dharma.

“In the ears of the Buddha as he thus sat in brilliant and sparkling craft of intuition, so that light like Transcendental Milk dazzled in the invisible dimness of his closed eyelids, was heard the unvarying pure hush of the sighing sea of hearing, seething, receding, as he more or less recalled the consciousness of the sound, though in itself it was always the same steady sound, only his consciousness of it varied and receded, like low tide flats and the salty water sizzling and sinking in the sand, the sounds neither outside nor within the ear but everywhere, the pure sea of hearing, the Transcendental Sound of Nirvana heard by children in cribs and on the moon and in the heart of howling storms, and in which the young Buddha now heard a teaching going on, a ceaseless instruction wise and clear from all the Buddhas of Old that had come before him and all the Buddhas a-Coming. Beneath the distant cricket howl occasional noises like the involuntary peep of sleeping dream birds, or scutters of little field mice, or a vast breeze in the trees disturb the peace of this Hearing but the noises were merely accidental, the Hearing received all noises and accidents in its sea but remained as ever undisturbed, truly unpenetrated, and neither replenished nor diminished, as self-pure as empty space. Under the blazing stars the King of the Law, enveloped in the divine tranquillity of this Transcendental Sound of the diamond ecstasy, rested moveless.”3

So this was my introduction to the Surangama Sutra. I, like Kerouac, fell under its spell. As for whether or not Kerouac used the ‘transcendental sound’ in his meditation practice, I do not know. But the fact that he could write about them so clearly, based on what he read in the Surangama Sutra, gave me hope that by bringing this practice, and the Surangama Sutra, to light, many more people could benefit from them.

In my case, I fell under the spell of this sutra, because, for the first time in my life, I had found a work that described my lifelong meditation practice accurately and completely, and even extended it in directions that I had not yet attained. I bring this up because it had a profound impact on my life. Not just in the sense of opening my mind to many new things — much of it only validated what I had already discovered and integrated into my life (or found that it was injecting into my life) — but in the sense of changing my intuitive path after that point.

The reason that I had hidden my meditative practice and contemplative insights from everyone, especially my closest friends and family members, was because I was experiencing profound changes in my understanding of myself and of this world, and whenever I would attempt to mention them, I would be invariably dismissed. But once I found the Surangama Sutra, I found my strength. It was like a gift, one that I hope to pass on to you.

Once I started writing about the sutra and my practice, I discovered that, although the Surangama Sutra is beloved in the Mahayana traditions of Buddhism in Central and Southeast Asia, and was once extant in India, it had been attacked in Tibetan Buddhism, and some quarters in Zen Buddhism for over 1,200 years. The reasons were mainly political, at first, and then because of the arrogance of certain individuals, who passed on unfounded criticisms that arose out of those politics, it became ‘common knowledge’ in Tibet, and no one came to its defense, so that over time, it was just forgotten. Meanwhile, in Chan Buddhism, it was, and is, one of the most beloved texts.

The criticisms were unjustified and not evidenced at all, and I present evidence in a later chapter that undermines each criticism by presenting actual historical records to clear its name, once and for all time. I am happy to relate the welcome news, however, that this state-of-affairs is now changing in Tibetan Buddhism, with the sutra itself being taught by at least one respected lama,4 who became my teacher, and even quoted in the work of another important lama’s5 writings.

Kerouac did not claim authorship of Wake Up, instead, he merely indicated that it was “prepared by” him. Was he accessing the wisdom of the Buddhas? Is that why he didn’t say that he was the author? I mention this because what he wrote in the quote above is his melding of the Surangama Sutra’s presentation of the power of the inner spontaneous sounds as a support for the Buddha’s meditation practice and his Dharma teachings, and necessarily that of all Buddhas. This will be presented in more detail later, but to give you a taste, here are the words found in the Surangama Sutra, by the Buddhist bodhisattva, Manjusri, who represents the transcendental wisdom of all Buddhas:

How sweetly mysterious is the Transcendental Sound of Avalokitesvara! It is the pure Brahman Sound.6 It is the subdued murmur of the sea-tide setting inward. Its mysterious Sound brings liberation and peace to all sentient beings who in their distress are calling for aid; it brings a sense of permanency to those who are truly seeking the attainment of Nirvana’s Peace. While I am addressing my Lord Tathagata, he is hearing, at the same time, the transcendental sound of Avalokitesvara.7

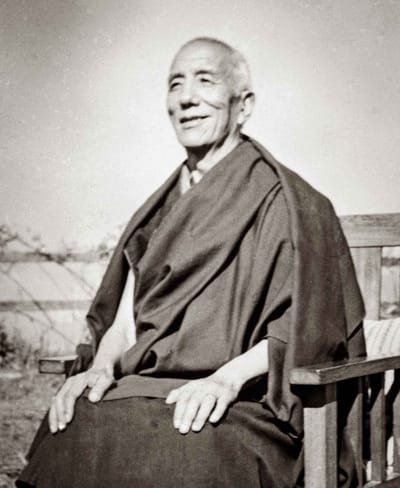

One last subject that I will be discussing in this work, that I must mention, is a prophecy for today, these times now, that was found in the papers of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, who passed away in 1959, in which the Buddha advises everyone to use the practice of Avalokitasvara during these troubled times, and the traumatic events that are now already happening. The Buddha calls this practice that everyone should be doing, Great Responsiveness Meditation. Yes, the same name. To my knowledge, these two uses of that name are the only ones where you will find this name used. This prophecy connects my knowledge about using the inner spontaneous sounds with the meditation technique of Avalokitasvara, and to both the Surangama Sutra and this prophecy.

The prophecy is not an ‘End-Time’ prophecy of terrible events. It lists specific trends that will be extant now, and every one of them is already indisputably present in our world, and explains how the Great Responsiveness Meditation of Avalokitasvara can help everyone manage the traumatic experiences that fill our daily newsfeed.

What it all means to you, I hope, will become clear as you read this book.

ཨེ་མ་ཧོ། ཕན་ནོ་ཕན་ནོ་སྭཱཧཱ།

Footnotes:

1 Wake Up — A Life of the Buddha, “prepared by” Jack Kerouac, 1955; published 2008, Viking

2 Robert A. F. Thurman is Jay Tsong Khapa Professor of Into-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University in New York, and one of the founders and the current president of Tibet House in New York City, as well as a longterm student of HH Dalai Lama, and a translator of various Tibetan Buddhist texts.

3 Text quoted from pgs 24-25 of Wake Up — A Life of the Buddha

Jack prefaced his book with a note. It said in part: “This book follows what the Sutras say. It contains quotations from the Sacred Scriptures of the Buddhist Canon, some quoted directly, some mingled with new words, some not quotations but made up of new words of my own selection.” and later: “The heart of the book is an embellished précis of the mighty Surangama Sutra whose author, who seems to be the greatest writer who ever lived, is unknown. He lived in the First Century A.D. and drew from the Brightest Divine Enlightenment.” (Quoted from Ibid., pg 5.)

4 Khenpo Sodargye, the head of the Tibetan Nyingma monastery of Larung Gar Five Sciences Buddhist Academy — the largest Tibetan monastery in the world — in the former Kham region of Tibet, taught the entire Surangama Sutra, starting in the Fall of 2019

5 Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche’s recently published a book, “Poison is Medicine” that quotes from the Surangama Sutra.

6 “Brahman Sound” refers to an earlier Hindu practice using inner spontaneous sounds as support.

7 The Surangama Sutra, in A Buddhist Bible, 2nd edition, Dwight Goddard, editor, 1952, page 257.