Cognizant Gravitation Only

This is a ‘physical’ reality encompassing materiality and nonmateriality as one indivisible reality. It is only our insistence that matter is all there is, that keeps us cemented in place.

[ Introduction | Fluid Motion As Evidence Of Biphasic Perception | What Creates Forms And Maintains Their Coherent Continuity? | What About Time? | Do Gravitational Fields Play An Essential Part In The Structuring of Forms? | Gravitation | The Development Of This Theory In The Paradox of Thinking Our Own Thoughts | Some Ramifications Of This Novel Theory | Summary | End Notes ]

Introduction

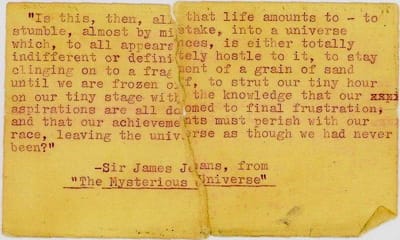

Sometime between my 10th and 12th year, I typed a question on a white index card in red ink, typos and all, and I still carry that card in my wallet to this day, decades later. The card is ripped in half, because sometime during my thirties, I believed that I had the answer. But after dropping the pieces into a waste basket, a doubt crossed my mind, and I retrieved them reluctantly. It was a question that was posed by the physicist, Sir James Jeans:1

Sir James was an idealist, and he saw idealism as a stance against the rampant materialism that was the mainstay of his profession. I was deeply affected by his thoughts, and for a long time I would have considered myself an idealist, if anyone had asked. My thoughts, though, are but a shadow of this world — a world of beauty which fills my days, whether I notice, or not. I could not see how abstractions could be fundamental to that beauty. So this question in my wallet troubled me, because I, like Sir James, could not accept that matter, and its random interactions, was all there is; nor could I accept that it was mentation.

But there was something else at play: my mother died when I was five, and being profoundly troubled by this, I learned how to put myself into a trance state to calm myself, and this led to a lifelong meditation practice which became the foundation of my attempts to answer Jean’s question. Traditional meditation practices have well-known progressions of insights, something that became problematic for me, being without a teacher. It wasn’t until I realized that my approach of accepting the worldview that I was being inculcated with, while trying to fit those meditative events into it, was backwards, that I came to see the world different.2

I have had a lifelong fascination with science, though I rebel at its seemingly arbitrary focus on matter, and the ‘omnific’ brain. Many details weren’t actually explained, I felt, especially how beings come to be, and how they proceed over time — they just did, little or no explanation needed.

I see a similar blindness today in the many, many theories of what ‘consciousness’ is, or rather, where it is and how it ‘emerges’ — answers to the wrong questions, it seems to me. What is worse, this abstract entity is then situated somewhere in the brain, or as some fundamental thing, or even as reality itself. It is set apart from that which it is ‘conscious of,’ and this is more properly a kind of clairvoyance — knowing from a distance — raising a question as to why we need senses, if we can be conscious from a distance.

The root of our difficulties, I submit, is that having conceptualized our being conscious as an abstract entity called ‘consciousness,’ we have created an insurmountable problem: without knowing what exactly we are abstracting consciousness from, we cannot advance a veridical3 theory, and without a veridical theory, we cannot place consciousness.

I start from a phenomenological understanding of how we are ‘conscious of’ — that which the concepts ‘awareness’ and ‘consciousness’ gloss over. Buried in those two abstractions is something more basic to both — something actual, yet impersonal; perspectival, but not subjective; a recognition, not a definition. I use the words cognizance and cognizant to point to this more basic nature of becoming aware or conscious.

The original meaning of cognizance comes from Latin cognoscere ‘getting to know.’ I use this word in that original sense. It is only a bare ‘recognition of’ — a liminal dawning of being aware, or conscious.

For example, we ‘take note of’ something and we either immediately recognize it, or fail to, in a first phase of perception. This recognition is the percept that we perceive — the actual immediate experience, which I call imperience — before any conceptual, qualitative, or historical decorations are applied. Normally, a second phase, that of ‘decorating’ the imperience with qualities, names, meanings, identities, classifications, relations, and history occurs. We ‘work out’ what this presence is, in a second phase of what I call biphasic perception.4

The recognition of imperience, is not language-based, nor conceptual, and is not subjective, it is impersonal, immediate, and actual. It is dimensionless, and thus, nondual. It carries with it, a sense, or feeling, of truth, and that truth pervades the percept.5 One could say that this is just ‘consciousness,’ but that would be to miss my point here entirely.

So, what is recognized, if not all of those qualities, names, meanings, etc.? It is the coherent continuity of that presence in successive moments. It is the produced fluid motion of our perceptions, our self, our body, and our life. It is the felt duration of our days, and of what is happening. This is the role that cognizance specifically plays. If there is no cognizance of the presence of what is actual in each moment, then there can be no duration, no fluid motion, and more to the point, there would be no continuity to our perceptions, nor to us. This, I argue, is the necessity for cognizance: without it, life could not form.

If the recognition fails, a second phase of inferential reasoning about what it might be is immediately commenced. Note that we are not conscious of this reasoning.6 We know it must be happening because of the computational complexity of the task of identifying an unknown. If successful, it will deliver a decorated experience — what we take away as knowledge, understanding, or ‘information.’ If this second phase fails, we are left in a state of bewilderment and must choose a path forward.

Sometimes, that second phase does not happen. We are habituated to these two-phases, and because they normally pass so quickly, we don’t even see them as phases. The result is that we live in our inferences and ideas, concepts and theories, memories, and traumas — not in our actual world and body. But sometimes, whether through training, exhaustion, or startle, we dally with the imperience, so the recognition can develop into a feeling of beauty — not as a judgement, but as a recognition of the perfection of each moment.

As well, something very magical can happen — if the second phase processing remains quiescent. This magical occurrence is the final ‘fledge’ of the recognition of presence into a feeling of divinity — an overflowing of the felt beauty of presence, an effulgence of the divine, a unitive return to origin. This is how ‘spontaneous spiritual awakenings’ can occur, and is the realization of our true nature. And it is here, from this, that everything in our life can change. Yet even in the face of this beauty, we seem, today, to want to abstract it, qualify it, turn it into alphabet soup.

Many traditional meditation practices have as a goal, the attenuation or suspension of the second phase entirely so as to have a direct experience of our true nature.